The Indus Valley Civilization (often dated broadly between c. 2500 and 1900 BCE for its mature phase) represents one of the world’s earliest urban cultures, flourishing in the northwestern regions of South Asia. It emerged during a period of significant human development, characterized by sophisticated societal organization that went beyond basic subsistence.

What Is Indus Valley Civilization?

- Early Urban Society: It was one of the three earliest widespread civilizations of the Near East and South Asia (alongside Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia), notable for its highly organized cities and advanced infrastructure for its time.

- Geographical Extent: The civilization spanned a vast area. Its reach extended from regions in modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan eastward to Northwestern India.

- Northernmost known site: Shortugai (Afghanistan) is often considered a key northern outpost, while Manda (Jammu and Kashmir, India) marks a significant northern presence within the core region.

- Southernmost extent: Reached towards Daimabad (Maharashtra, India) in its later phases.

- Easternmost site: Alamgirpur (Uttar Pradesh, India).

- Westernmost site: Sutkagendor (Pakistan, near the Iran border).

- Location Factors: Most settlements were strategically located along the plains of the Indus River and the now largely dried-up Ghaggar-Hakra river system, with coastal sites also playing a crucial role, likely for trade.

- Archaeological Significance: The IVC is known almost entirely through archaeological discoveries, as its script remains undeciphered. Extensive excavations continue to reveal insights into its culture, technology, and society.

- Trade Networks: Evidence indicates well-established trade links with contemporary civilizations, including Mesopotamia (Sumerians in modern-day Iraq) and regions around the Persian Gulf.

Chronology:

Archaeologists generally divide the Indus Valley Civilization into the following periods (note that dates are approximate and can vary slightly between sources):

- Pre-Harappan/Early Food Producing Era: c. 7000 – 3300 BCE (Developments leading towards urbanization)

- Early Harappan: c. 3300 – 2600 BCE (Formation of larger settlements, early urbanism)

- Mature Harappan: c. 2600 – 1900 BCE (Peak of urbanization, sophisticated cities, widespread culture)

- Late Harappan: c. 1900 – 1300 BCE (Decline, fragmentation, shift in settlement patterns)

- Post-Harappan Transition: Following the decline, the region saw the emergence of different cultural phases, eventually overlapping with the early Vedic Period (typically dated c. 1500 – 500 BCE).

Important Archaeological Sites:

Some of the most significant excavated sites include:

- Mohenjo-daro (Pakistan)

- Harappa (Pakistan)

- Kalibangan (Rajasthan, India)

- Lothal (Gujarat, India)

- Dholavira (Gujarat, India – located in the Kutch region)

- Rakhigarhi (Haryana, India)

- Ganeriwala (Pakistan)

- Chanhudaro (Pakistan)

- Kot Diji (Pakistan)

- Surkotada (Gujarat, India)

- Alamgirpur (Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Banawali (Haryana, India)

(Note: Kutch is a large district in Gujarat containing multiple Harappan sites like Dholavira and Surkotada, rather than being a single site itself. Desalpur is another site within Kutch).

Important Indus Valley Civilization Sites and Discoveries

The Indus Valley Civilization is known through numerous archaeological sites. Here are some of the most significant, along with their key findings:

Major Urban Centers:

Mohenjo-daro (Sindh, Pakistan)

- Location: Banks of the Indus River.

- Excavator Highlight: R.D. Banerji (initial discovery, 1922).

- Key Discoveries:

- The Great Bath (a large public water structure).

- Extensive granaries for grain storage.

- The iconic bronze statue of the “Dancing Girl.”

- Steatite seal depicting a figure often identified as “Pashupati” (proto-Shiva).

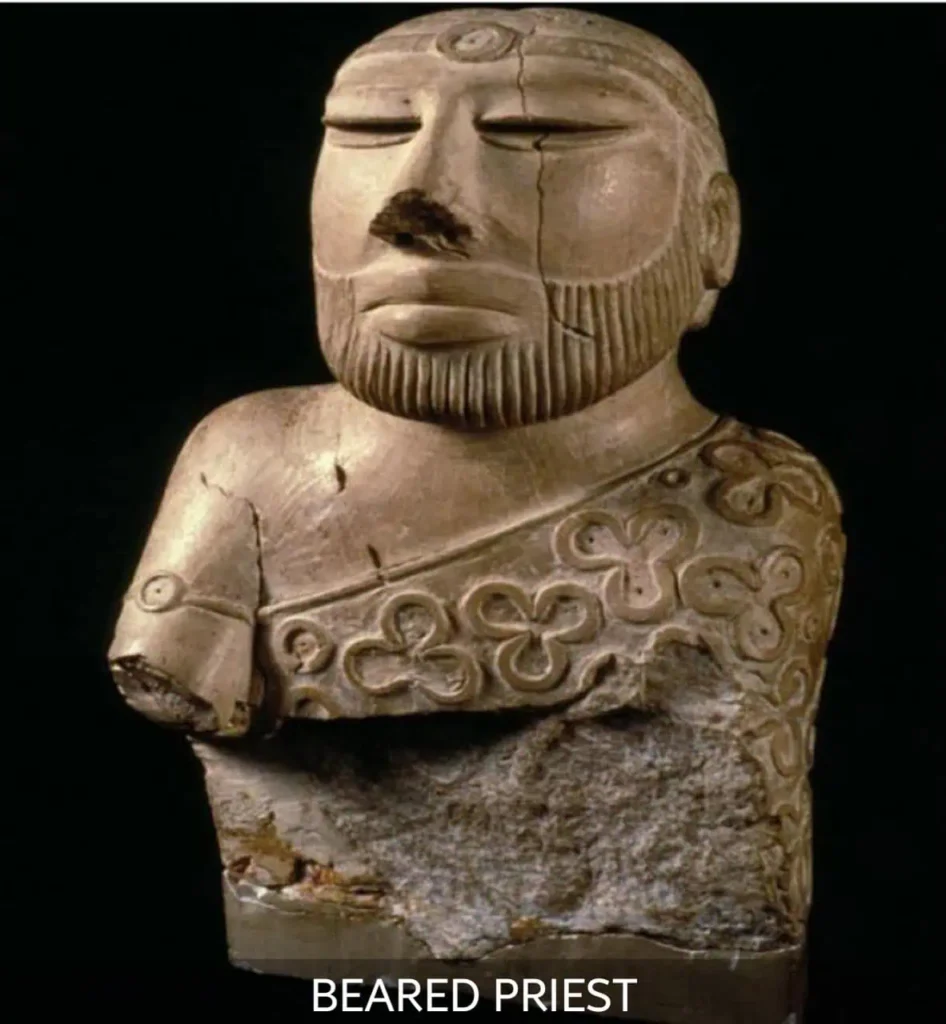

- Stone sculpture fragment known as the “Priest-King” (bearded man with trefoil pattern shawl).

- Terracotta figurines (e.g., Mother Goddess).

- Evidence of cotton textiles.

Harappa (Punjab, Pakistan)

- Location: Banks of the Ravi River (a tributary of the Indus).

- Excavator Highlight: Daya Ram Sahni (extensive work, 1921-1923).

- Key Discoveries:

- Large granaries arranged in rows, often with associated workers’ quarters.

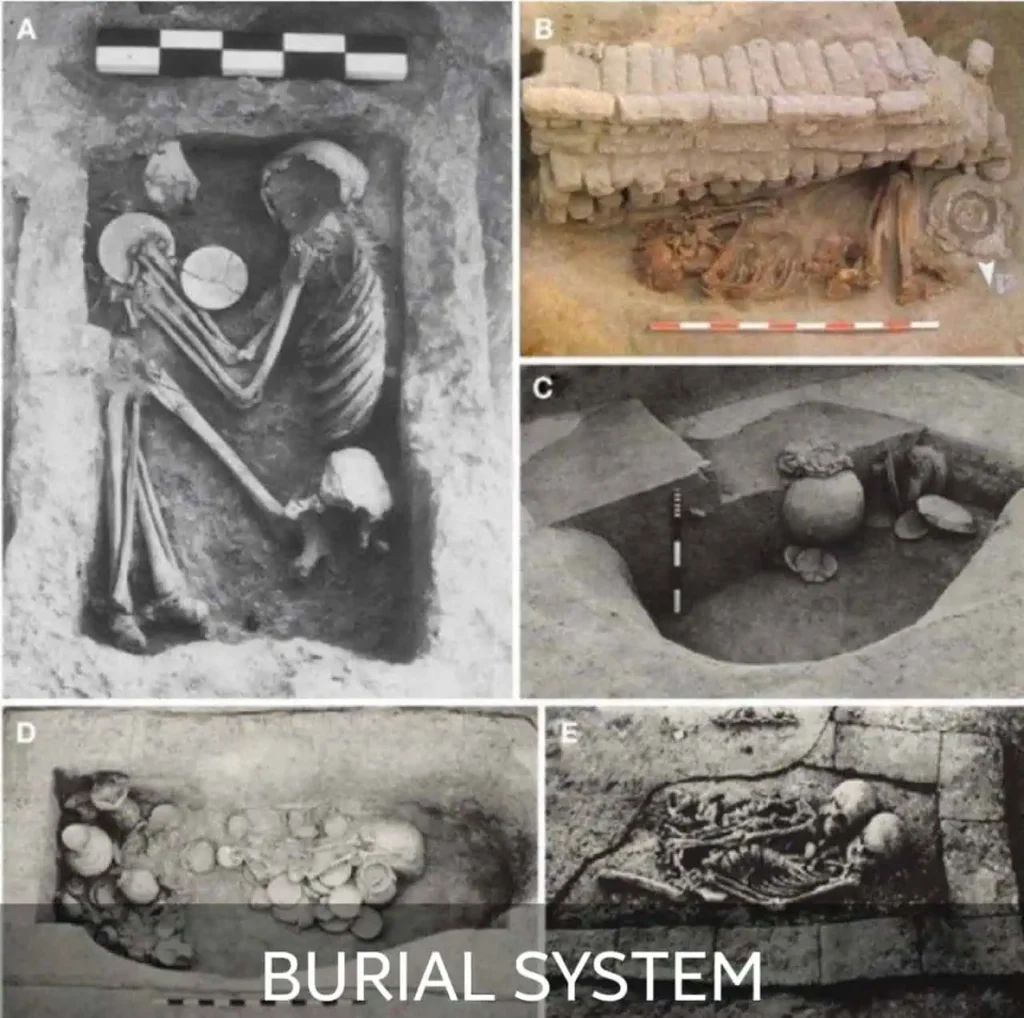

- Systematic burials in cemeteries, notably “Cemetery R-37.”

- Evidence of coffin burials (less common).

- Skeletal remains, including some skulls showing evidence of trepanation (holes drilled, possibly for medical or ritual reasons – significance still researched).

Dholavira (Kutch, Gujarat, India)

- Location: Khadir Bet island, Rann of Kutch (associated with Mansar/Manhar streams).

- Excavator Highlight: J.P. Joshi (discovery & initial work, 1967-68), R.S. Bisht (extensive excavations later).

- Key Discoveries:

- Elaborate water conservation and management system (reservoirs, channels).

- Unique city layout with distinct middle town, besides citadel and lower town.

- Extensive use of stone in construction (alongside brick).

- A large inscription of 10 large Indus signs (“signboard”).

Note: Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site on July 27, 2021. (Evidence for horse remains is sometimes cited but remains debated among scholars).

Rakhigarhi (Haryana, India)

- Location: Near the now-dry Drishadvati River (part of the Ghaggar-Hakra system).

- Excavator Highlight: Discovered early, significant work by Dr. Amarendra Nath (ASI) from the 1990s onwards; ongoing research by various teams.

- Key Discoveries:

- One of the largest IVC sites, potentially exceeding Mohenjo-daro in area.

- Evidence spanning Early, Mature, and Late Harappan phases.

- Planned settlements with mud-brick and burnt-brick houses, streets, drainage.

- Rich material culture: seals, pottery, terracotta figurines, copper/bronze objects, stone tools, beads.

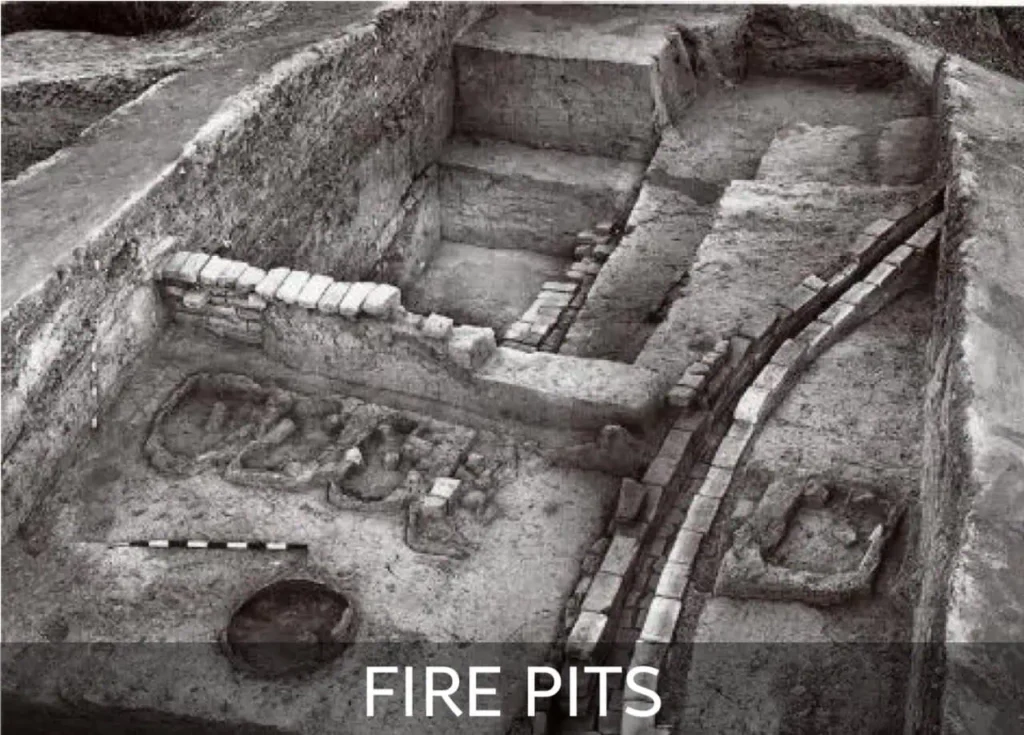

- Fire altars, burials, potential jewellery workshops.

Kalibangan (Rajasthan, India)

- Location: Banks of the Ghaggar River (identified by some with the ancient Sarasvati).

- Excavator Highlight: A. Ghosh (discovery), B.B. Lal & B.K. Thapar (excavations, 1961 onwards).

- Key Discoveries:

- Evidence of the earliest known plowed field (Early Harappan period).

- Fire altars, suggesting ritual practices.

- Evidence of potential earthquake damage and rebuilding.

- Distinctive pottery and terracotta figurines.

- Possible evidence for double cropping patterns.

Lothal (Gujarat, India)

- Location: Near the Bhogavo River (flows into the Sabarmati River system/Gulf of Khambhat).

- Excavator Highlight: S.R. Rao (1954 onwards).

- Key Discoveries:

- A large structure identified as a tidal dockyard, indicating maritime trade.

- Warehouse structure near the dock.

- Bead-making workshops.

- Evidence of rice cultivation (relatively rare in Mature Harappan sites).

- Double burials (two individuals interred together).

- Terracotta models (e.g., ship, plough).

Note: Sometimes referred to metaphorically as an ancient “Manchester” due to its trade/industrial focus, not literal crop production dominance.

Chanhudaro (Sindh, Pakistan)

- Location: Along the Indus River.

- Excavator Highlight: N.G. Majumdar (1931), later Ernest Mackay.

- Key Discoveries:

- Major center for craft production: bead-making factory, evidence for seal cutting, metalworking.

- Terracotta models, inkpot.

- Evidence suggesting it was a city without a fortified citadel.

- Famous find: imprint of a dog’s paw chasing a cat’s paw in baked brick.

Alamgirpur (Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Location: Banks of the Hindon River (tributary of Yamuna).

- Significance: Represents the easternmost known extent of the Harappan culture.

- Key Discoveries: Primarily Late Harappan material; finds include typical pottery, ceramic items, some copper objects (like a broken blade), evidence of cotton use.

Surkotada (Kutch, Gujarat, India)

- Location: Kutch district.

- Excavator Highlight: J.P. Joshi (1964 onwards).

- Key Discoveries:

- Fortified settlement with stone rubble fortifications.

- Evidence of occupation through Mature and Late Harappan phases.

Note: Famous for disputed claims of horse remains found here. Played a role in regional trade/control.

Kot Diji (Sindh, Pakistan)

- Location: Near the Indus River, opposite Mohenjo-daro.

- Significance: Important pre-Harappan and early Harappan site, showing cultural layers preceding the mature phase. Evidence of a major fire separating periods.

- Key Discoveries: Distinctive pottery styles (“Kot Dijian”), evidence of early fortifications, terracotta figurines (e.g., bull, mother goddess).

Desalpur (Kutch, Gujarat, India)

- Location: Kutch district.

- Significance: Fortified Harappan town showing regional characteristics.

- Key Discoveries: Massive stone fortification, Harappan pottery, three script-bearing seals (steatite, copper, terracotta).

Indus Valley Civilization- Art and Architecture

Architecture & Town Planning:

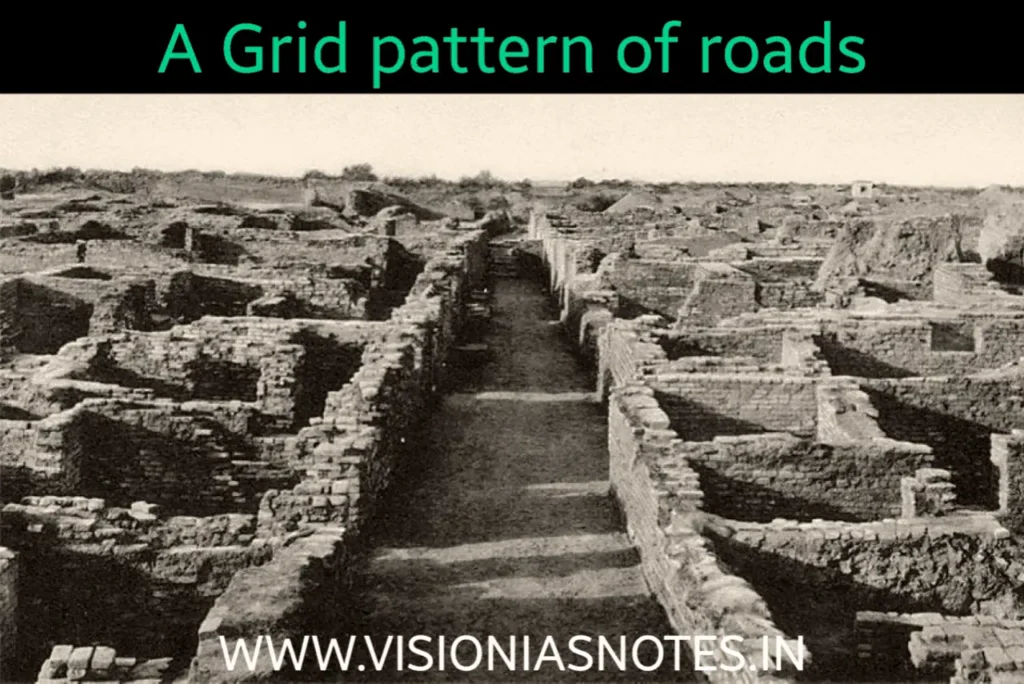

- Urban Layout: Cities often featured sophisticated planning, typically based on a grid pattern with main streets oriented north-south and east-west, intersecting at right angles. Smaller lanes branched off to access individual houses.

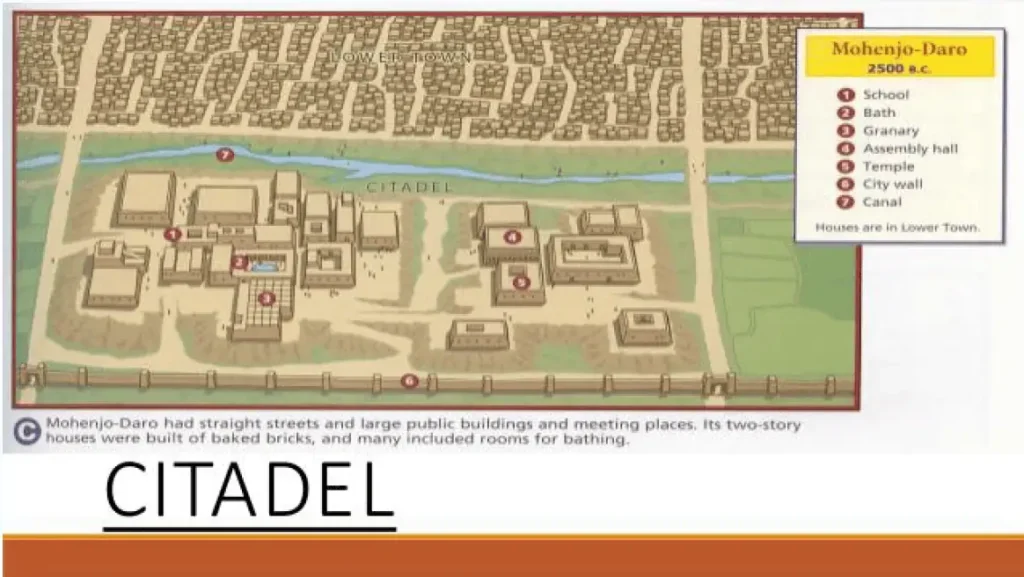

- City Division: Many larger cities were divided into two main parts:

- Citadel: A raised, fortified area, usually to the west. It contained major public structures like granaries, administrative buildings, assembly halls (pillared halls), and significant ritual structures (e.g., the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro).

- Lower Town: The larger residential area to the east, where the general populace lived and worked. Houses were typically built around courtyards.

- Building Materials: Baked bricks of standardized proportions were widely used, alongside mud bricks, timber, and stone (especially in areas like Gujarat).

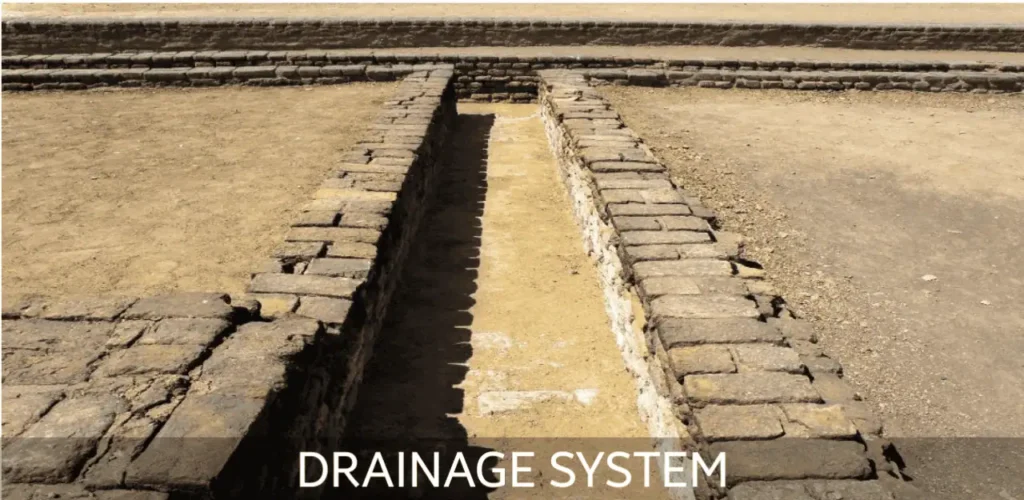

- Drainage System: A remarkable feature was the advanced sanitation system. Houses had bathrooms connected by drains to larger covered sewers running beneath the main streets. These included inspection holes/manholes (cesspits) for maintenance.

Sculpture and Crafts:

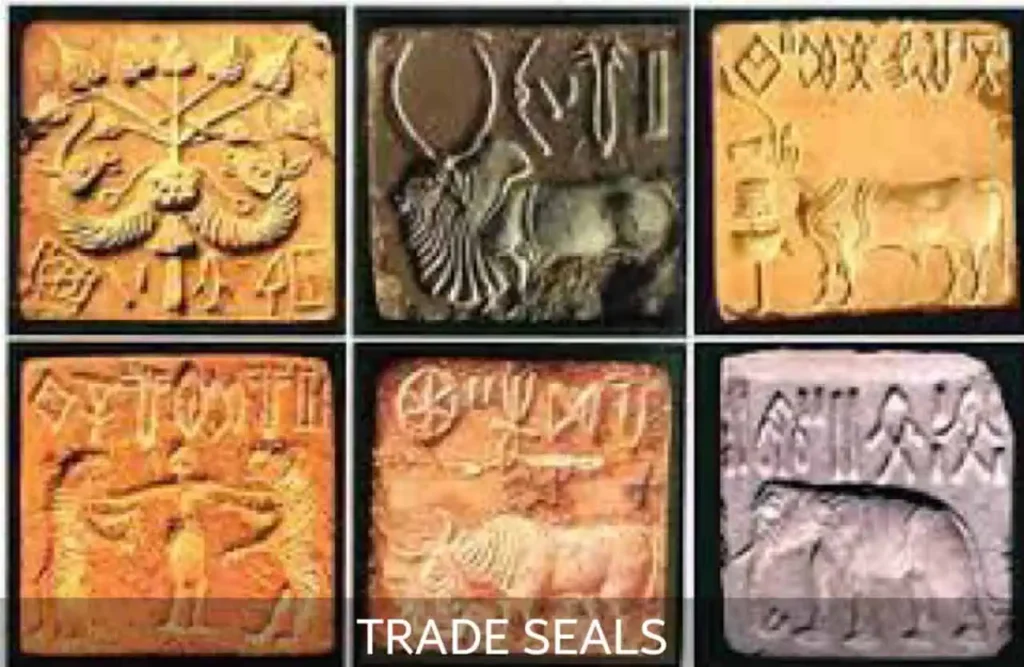

- Seals:

- Function: Used primarily for trade (marking ownership/origin of goods), administration, and possibly as amulets or identification markers.

- Materials: Most commonly made of steatite (soft stone), but also copper, faience, ivory, and terracotta.

- Shape: Typically square or rectangular, but also circular and cylindrical. Often perforated for suspension.

- Motifs: Intricately carved with figures of animals (especially bulls, unicorns, elephants, rhinos), human or composite figures (like the “Pashupati” seal), and Indus script.

- Bronze Figures:

- Technique: Mastered the lost-wax method (cire perdue) for casting.

- Examples: The iconic “Dancing Girl” from Mohenjo-daro (notable for its Tribhanga posture and ornamentation), bronze carts, animals.

- Terracotta Figures:

- Technique: Fire-baked clay used extensively.

- Subjects: Numerous figurines of humans (especially “Mother Goddess” figures), animals, birds, toys (miniature carts, wheels), and game pieces. Often simply modeled but expressive.

- Stone Figures:

- Skill: Demonstrates high craftsmanship, though fewer large stone sculptures survive compared to Egypt or Mesopotamia.

- Examples: The “Priest-King” bust (steatite) from Mohenjo-daro, known for its detailed shawl and meditative expression. A red sandstone male torso from Harappa, noted for its naturalistic modeling.

- Pottery:

- Types: Both plain utilitarian ware and fine painted pottery were produced. Most were wheel-made.

- Painted Ware: Often features a distinctive Red and Black Pottery style – red slip background with geometric patterns, trees, birds, and animal figures painted in black.

- Uses: Household storage, cooking, serving liquids, decorative purposes, and sometimes used in burials.

Language and Script:

- Indus Script: The civilization had a written script, found primarily on seals, pottery, and other artifacts.

- Characteristics: It is pictographic, containing several hundred unique signs. It was typically written from right to left, although some longer inscriptions show a boustrophedon style (alternating directions line by line).

- Status: Despite numerous attempts, the Indus script remains undeciphered, hindering a full understanding of their language, beliefs, and governance.

Society and Daily Life in the Indus Valley Civilization

Archaeological evidence allows us to reconstruct aspects of the daily lives of people during the Indus Valley Civilization:

- Food Habits:

- Agriculture: Key staples included wheat and barley. Other cultivated crops were peas, sesame seeds, dates, mustard, and cotton.

- Diet: Their diet likely included fruits such as pomegranates and possibly bananas. Animal bones indicate the consumption of meat (from cattle, sheep, goats, pigs) and fish.

- Clothing and Adornment:

- Materials: Textiles were primarily made from cotton, with evidence suggesting wool was also used.

- Attire: Figurines suggest women may have worn short skirts and significant jewelry, while men might have worn a cloth wrapped around the lower body, sometimes with a shawl. These are interpretations based on artistic depictions.

- Ornaments: Both men and women likely adorned themselves. Discoveries include necklaces, bracelets, bangles, rings, and beads made from materials like shells, terracotta, faience, copper, bronze, silver, and gold. Amulets were also worn, possibly for protection or status.

- Recreation and Leisure:

- Children’s Toys: Numerous terracotta toys have been found, including small carts, animal figurines, dolls, rattles, marbles, and bird-shaped whistles. Some animal figures may have functioned as puppets.

- Adult Activities: Dice and objects identified as game boards suggest games of chance, like gambling, were enjoyed by adults.

Economy and Trade of Indus Valley Civilization:

- Occupations: The society supported various specialized professions, including:

- Farming and animal husbandry.

- Pottery making.

- Weaving of cotton and wool textiles.

- Extensive craft production, particularly bead-making (using carnelian, steatite, faience, shell, terracotta, ivory, etc.).

- Metalworking (copper, bronze, gold, silver).

- Construction and brick-making.

- Seal carving.

- Trade.

- Trade Networks: The IVC engaged in extensive trade, both locally and internationally:

- Evidence: Standardized weights and measures (found notably at Lothal) facilitated commerce. IVC seals and characteristic objects found in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and sites around the Persian Gulf (like Oman) attest to long-distance trade.

- Goods: Traded goods likely included grain, textiles, timber, beads, shells, metals, and finished craft items. They imported raw materials like Lapis Lazuli (a blue gemstone) from Afghanistan, turquoise from Persia, and copper and shells from various regions.

Belief Systems of Indus Valley Civilization (Religion):

- Interpretation: Understanding IVC religious beliefs is challenging due to the undeciphered script. Interpretations are based on figurines, seals, and structures.

- Deities: Numerous terracotta figurines, often identified as “Mother Goddesses,” suggest worship related to fertility. The famous “Pashupati seal” depicts a seated, horned figure surrounded by animals, interpreted by some as a proto-Shiva or nature deity.

- Sacred Symbols/Elements: Certain motifs appear frequently and may have held religious significance, such as the Peepal tree, bulls (especially the humped bull), and horned figures found on seals.

- Ritual Practices: Fire altars discovered at sites like Kalibangan and Lothal suggest ritualistic use of fire. Burial customs, which varied over time and region, also offer insights into their views on death and the afterlife.

The Decline of the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 1900 – 1300 BCE)

The flourishing urban phase of the Harappan civilization gradually declined starting around 1900 BCE, leading to the abandonment of major cities and a shift in population eastward. There is no single, universally accepted cause for this decline; it was likely the result of multiple converging factors:

- Environmental & Climate Change:

- River System Changes: Tectonic activity or natural sedimentation may have altered the courses of major rivers, including the Indus and the Ghaggar-Hakra (often identified with the ancient Saraswati). The drying up or shifting of these vital water sources would have devastated agriculture.

- Climate Shifts: Evidence suggests the climate grew cooler and drier around this period. Changes in monsoon patterns (either weakening or shifting eastward) could have led to prolonged droughts, impacting harvests and water availability.

- Flooding: Conversely, massive, destructive floods in parts of the Indus basin are also proposed as a contributing factor in some areas (as depicted speculatively in popular media like the film Mohenjo Daro).

- Resource Depletion & Ecological Stress: Centuries of intensive agriculture, deforestation for fuel (brick-making) and timber, and grazing may have degraded the landscape, reducing its capacity to support large urban populations.

- Migration and Societal Shifts:

- Aryan Migration: While the older theory of a violent Aryan invasion and conquest is now largely discounted by scholars, the gradual migration of Indo-Aryan speaking groups into the region during this period likely occurred. The interaction and potential conflicts or integration with the declining Harappan populace may have played a role in cultural transformation.

- Population Movement: As cities declined, populations seem to have migrated eastward towards the Ganges plain and south into Gujarat, establishing smaller, more rural settlements. This indicates a decentralization and transformation rather than a complete collapse.

- Other Potential Factors:

- Disease: Some researchers speculate that outbreaks of infectious diseases (epidemics) could have weakened the population.

- Decline in Trade: Disruptions to long-distance trade networks could have impacted the urban economy.

Conclusion:

The decline of Indus Valley Civilization was likely a complex, gradual process driven primarily by environmental changes impacting the river systems and agriculture, possibly exacerbated by ecological degradation and societal shifts including migrations. Research continues to refine our understanding of this transition period.